A3 - Root Cause Analysis

The A3 is a tool for identifying root causes to deep problems and building consensus on how to remedy them.

Estimated time for this content: 20 minutes

Audience: Scrum Masters facing a reoccurring impediment

Suggested Prerequisites: Retrospective, Muda

Upon Completion you will:

- Have a base-line knowledge of lean principals as practiced by Toyota

- Know how lean and agile practices utilize the Plan Do Check Act cycle

- Understand the pre-cursors to doing root cause analysis

- Understand how to perform root cause analysis

- Be able to complete a step-by-step process for the A3

Overview

The A3 tool was pioneered by Toyota to document and address problems with their production process. Anyone at Toyota can initiate the process and they do it for almost all problems they encounter. To capture their analysis, they use the largest sheet of paper that fit into a copy machine, the A3 or Tabloid (two 8.5x11 sheets side-by-side.)

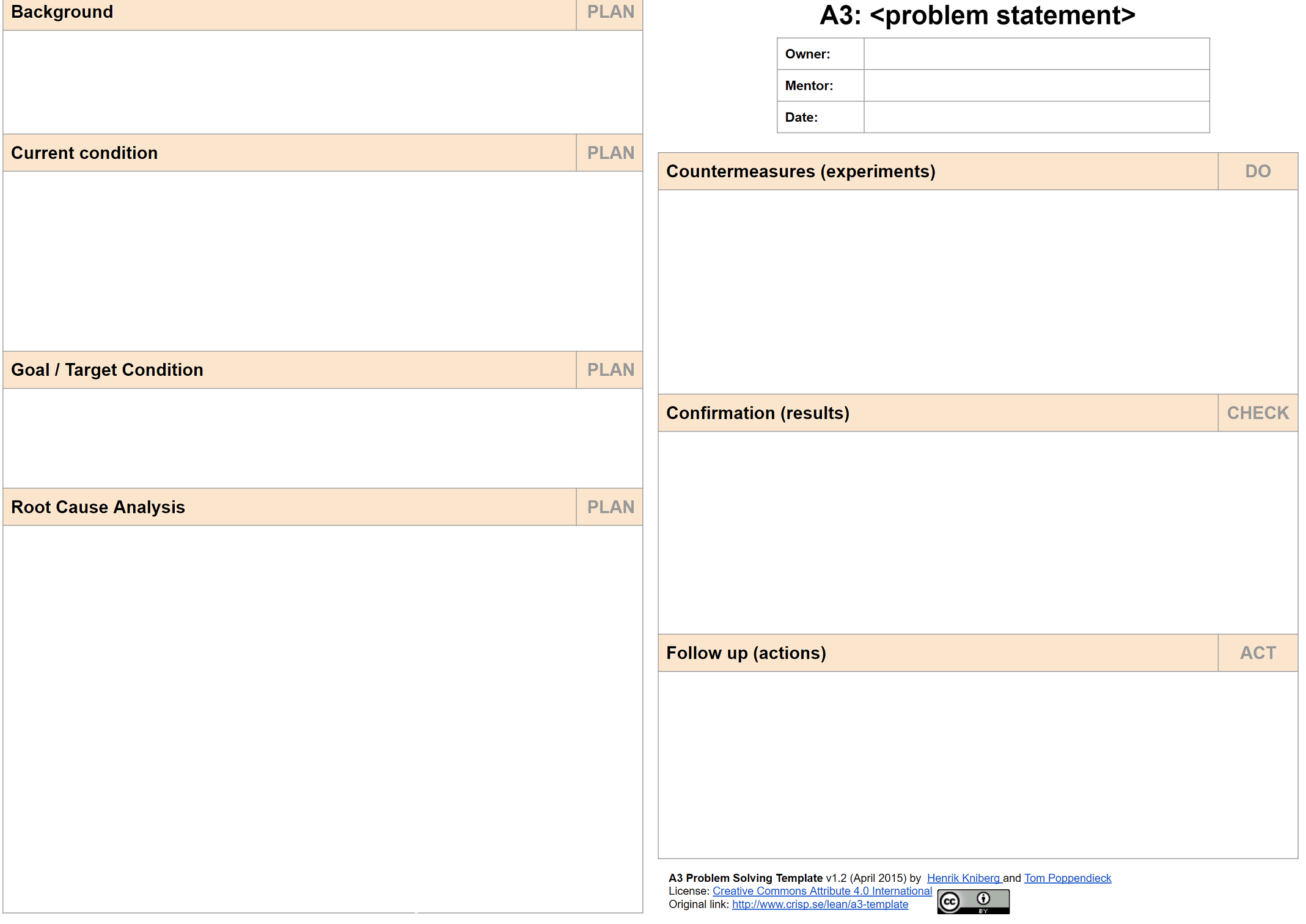

The A3 process is based on the Plan, Do, Check, Act, or PDCA Cycle. To initiate the A3 all the stakeholders should gather. The owner is the person who is responsible for ushering the process through to its end and the mentor is typically a high-ranking executive who can help implement the actions that result from the process. An A3 is meant to simplify complex problems, so using just one large sheet of paper follow the example in the slides. The title should be something catchy so it is easy to remember and to refer to.

A3 Template

A3 Template in Google Docs (Opens in a New Tab)

A3 Problem Solving Template v1.2 (April 2015) by Henrik Kniberg and Tom Poppendieck

License: Creative Commons Attribute 4.0 International

Original link: http://www.crisp.se/lean/a3-template

Step 1: Plan

The first cell is used to describe the background of the problem. It is important that all stakeholders participate in this phase so everyone involved has a clear idea of what the problem is. The A3 is a process so even if the problem is obvious, it is important to discuss it and make sure everyone is literally on the same page. Often, the background is a macro problem that affects multiple parts of the Scrum process.

With the background established, the discussion moves on to establishing the current conditions. This will be a list of symptoms like decreased Velocity or poor morale. It is important to make sure that the group is able to include some Metrics in this cell. Loss of revenue is always helpful because it gets management’s attention but any number of metrics will do. The important part is that they are precise and measurable.

Next, the group should decide on what the ideal outcome will be when the problem is solved. (The ideal state is similar to an Acceptance Test or Definition of Done for a Product Backlog Item.) Metrics are helpful here as well. It is important to have a well-defined target condition because it will help align all stakeholders around a common vision.

The last part of the planning phase is root cause analysis (see video) and this is the core of the A3. Establishing the problem and what life will be like after the problem is solved is relatively easy, agreeing on what the root causes are may involve some uncomfortable truths.

It sounds very high minded, but quality root cause analysis actually requires channeling your inner five-year old. The technique is called the Five Whys. Basically, the group needs to start with the most obvious problem and ask why. Here is an example:

Sprints are failing.

“Why?”

A: People think that the Team is lazy.

“Why?”

A: Because morale is low.

“Why?”

A: The Team is getting mixed messages from the Product Owner.

“Why?”

A: The Product Owner is getting conflicting orders from two managers.

“Why?”

A: The organization incentivizes competition rather than cooperation.

The point of the exercise is to get at least five layers deep into any problem. Five layers is a general rule of thumb. Root causes can be found three or seven layers deep. It is really important to invest a lot of time here. Often the stakeholders think they have arrived at a few root causes only to have to repeat the process later. Another good rule of thumb is that once the group thinks it has discovered the root causes, they should then put in again as much time as they’ve just spent. It is important to be exhaustive. (There are other root cause analysis techniques. A variety can be found here.)

There will likely be multiple root causes to a problem. In the above example, the Product Owner role has broken down, managers are probably talking to the team outside of their scope and the organization’s incentives are flawed.

Finding a root cause is a bit of an art. Here are a few characteristics to help guide your process: first, a root cause will resonate with stakeholders. Second, root causes also tend to be actionable, meaning that the group will have an idea how to approach the specific challenge. And, third it will have a certain amount of specificity. In the above example, “people think the Team is lazy” doesn’t have any granularity. Further inquiry helped pinpoint a more detailed root cause.

Step 2: Do

In Systems Theory, if multiple solutions are implemented at once, it is impossible to trace the effect of each. Therefore, it is important to implement only one solution at a time. The A3 is a living document so the group should continually note the results of each solution implemented and update the A3 as conditions change.

Step 3: Check

It is important to confirm that the countermeasure has the ideal state identified in step one. In order to know if the countermeasure worked, it is important to have objective criteria to judge it against. That is why having metrics in the current and target conditions makes for a better A3. It may be that multiple countermea

Step 4: Act

Hard Truths

When an A3 fails it is usually because the group didn’t delve deep enough into the problem or that the problem was beyond the ability of the team to solve or recognize. Solving the root cause can be the end result of a successful A3. However, that’s not always the case. A successful A3 can show that the root cause is beyond the ability of the organization to change like in the above example where there wasn’t enough market demand for the product. A good A3 can reveal deep challenges within the organization like conflicting core values, poor leadership or a critical lack of resources. The A3 isn’t a silver bullet; rather it’s a tool to bring transparency to dysfunction. How the stakeholders handle the dysfunction is their responsibility.